Happy Birthday Captain Ross

Today would have been Donald K. Ross’ 114th birthday. Let’s remember him.

Warrant Officer Machinist Mate Donald K. Ross, United States Navy

The crew, at parade rest with bowed heads, is standing in ranks, topside on the USS Nevada (SSBN 733). The submarine has made a rare stop, surfacing in the Pacific Ocean, just south of the island of O`ahu. The weather is splendid, with calm breezes that flutter the crisp white bell-bottom trousers, or gently tug at freshly rolled neckerchiefs.

Members of the rifle detail can barely hear the murmur of the commanding officer as he reads scripture. Standing farther aft, it doesn’t matter; their thoughts are focused on their upcoming role in the ceremony. The bugler is just as attentive, but he stands on the opposite end of the formation, forward, and closer to the sail facing aft.

“Crew!” barks a chief, “Hand — Salute!”

The commanding officer continues reading, while the Chief of the Boat readies the funeral urn, a box, containing the remains. He hands it to the officer designated to scatter the ashes. With a slight nod to the captain, the officer leans carefully out over the lifelines with arms extended and pours.

“Unto Almighty God, we commend the soul of our brother, Donald Kirby Ross, departed, and we commit his body to the deep, in sure and certain hope of the resurrection unto eternal life, through our Lord, Jesus Christ, amen.”

Soon after comes the chaplain’s benediction, ending the religious portion of the ceremony.

Then the chief again. “Present — Arms!”

After the reading and the prayers, three sharp cracks from the rifle salute. The sound of the bugle comes too soon. It always comes too soon. In just ten minutes, the Navy has paid tribute to Ross, one of the first Medal of Honor recipients of World War Two.

But who was Donald K. Ross?

EARLY LIFE

Donald Kirby Ross was born in Beverly, Kansas on December 8, 1910. The census that year recorded a population of only 335. Less than half that number live there today.

The town is located near the center of Lincoln County, which itself, is near the center of the state. With the state of Kansas near the center of our country, it is no surprise that Ross himself seems to have been a centered man: balanced, grounded, and anchored. He was sure of himself and sure of his abilities.

He enlisted in the Navy in Denver, Colorado in June 1929, and was his company’s Honor Graduate when he completed Basic Training in San Diego, California. After graduating first in his class at Machinist’s Mate School in Norfolk, Virginia, he progressed steadily through the ranks with several duty assignments before being promoted to Warrant Officer Machinist in October 1940. Ross’ courageous conduct aboard the USS Nevada during the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor would earn him recognition as being one of the war’s first Medal of Honor recipients.

DAY OF VALOR

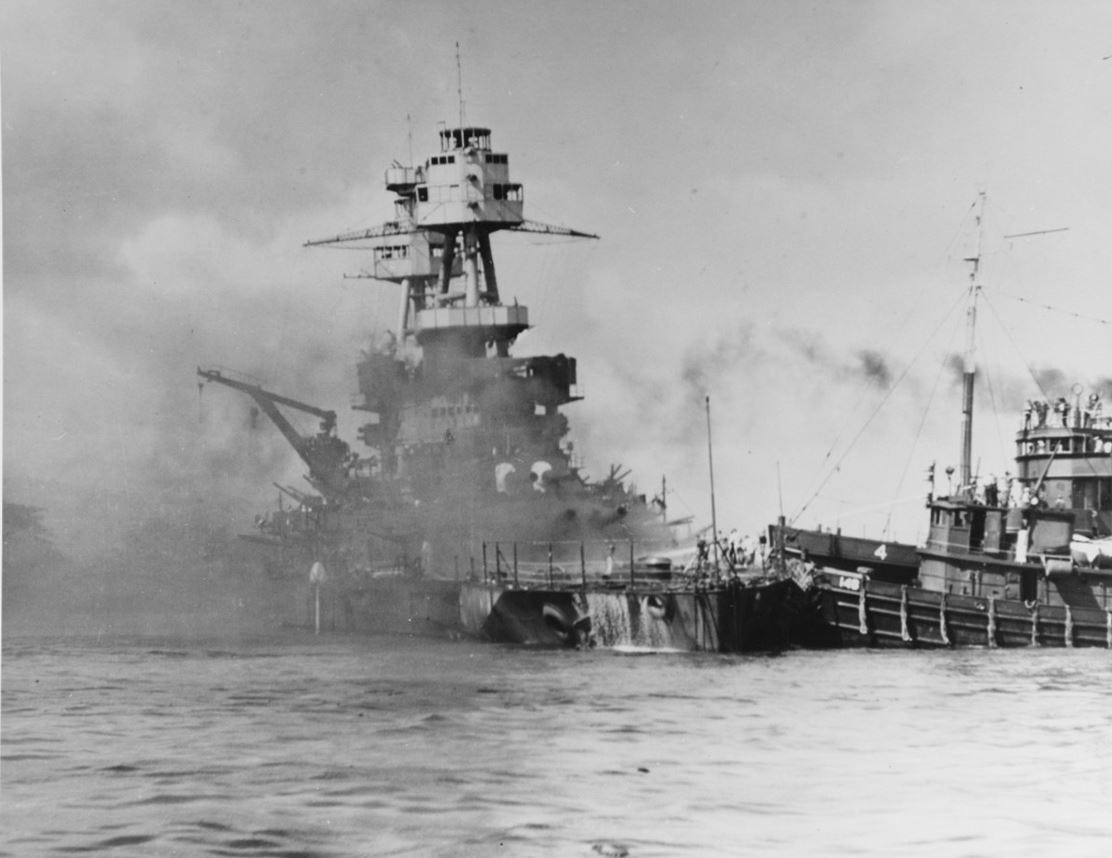

With the slam of a hatch, someone finally secured the forward dynamo room because of flooding. It was one p.m. on December 7, 1941. For the past five hours, the exhausted crew of the battleship Nevada had either been fighting the Japanese air attack or the raging fires that still threatened their ship.

In an interview given after the 50th anniversary of the attack, Ross described shaving in his stateroom just before the attack. He thought the first explosion he heard that morning was part of an Army exercise on Ford Island. The second explosion was much closer. Looking through the porthole, rising black smoke on the island’s airfield convinced him the harbor was under attack.

Machinist’s Mates, Boilermakers and Water Tenders operate and maintain the ship’s propulsion machinery and auxiliary equipment. Collectively called “Snipes,” they work in hot, dark engineering spaces well below decks.

Phoning from his stateroom, he directed the engineering division chiefs and sailors on duty to make ready for getting underway. “I’ll be ready to answer bells in 30 minutes,” he told them. Incredulous, they did not believe him — that’s not enough time. Ross yelled into the phone so those below could hear him above the din, reminding them, “I’ve got hot boilers!”

Unlike the other battleships, Nevada had kept her steam up, never letting all boilers go cold. The dreadnaughts moored in pairs along the quays, as they usually were, but Nevada was alone at the northern end of Battleship Row, a position that allowed greater freedom. This stroke of luck, along with the courageous work of the crew, enabled Nevada to get underway during the attack. The oldest battleship moored on Battleship Row that morning was the only battleship to get underway.

DYNAMO

With fires raging, the ship moved steadily south towards the channel’s mouth. The ship had sustained a torpedo hit during the first wave of Japanese aircraft and was attempting to get to the open ocean when the second wave of attackers arrived overhead.

Weeks before the attack, Ross had discovered that one of his sailors was only fifteen years old, and he probably realized many others were not much older. Now, in the thick of battle, he chased his 27 sailors out of the forward dynamo (generator) room.

“If you’re trained as a professional leader…” he later remarked, “your men are the most important thing in the world,” adding, “even more important than you are to yourself.”

He performed the duties himself, supplying needed electrical power until overcome by smoke, steam, and heat. Rescued and resuscitated, Ross then proceeded to operate the aft dynamo room, again single-handedly. Dipping his skivvy shirt into a drip pan, he wrapped the wet cloth around his face.

He was found unconscious yet again, this time nearly blind, but he returned to his station after being resuscitated. “I was alive — I was breathing — I could find my way.”

After several more bomb strikes and near misses, the crew grounded Nevada near Hospital Point to keep the channel clear, and the entrance to dry docks free and operational.

Years later, Ross would point out that the crew continued to fight fires well into the evening. Despite suffering serious wounds, Ross rebuffed hospitalization to remain involved in those efforts to save his ship. Why?

“Actually —” he said, “I think we give our souls to the ship, and she becomes a living thing to us.”

AFTER THE ATTACK

After Ross recovered his vision and returned to full duty, he remained aboard Nevada for the duration of the war. Promoted to Chief Warrant Officer in March, then as an Ensign in June 1942, he was part of ship’s company at both Operation Overlord (the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944) and Operation Dragoon (the Allied invasion of southern France, in August 1944). He went on to serve a total of 27 years in the Navy and was promoted to captain upon his retirement.

LATER LIFE AND DEATH

After retiring, Ross settled in Port Orchard, Washington, and ran a dairy farm with his wife Helen. The couple had four children: Fred, Robert, Penny, and Donna.

As an author, he published two books with his wife, “Washington State Men of Valor” (Coffee Break Press, 1980), and “0755: The Heroes of Pearl Harbor” (Rokalu Press, 1988).

Donald Ross died of a heart attack on May 27, 1992. At the time of his death, he was the oldest surviving recipient of the Medal of Honor. To acknowledge his service and honor his memory, six hundred guests joined the family aboard the USS Nimitz, the ship named for the naval hero that had presented Ross the Medal of Honor fifty years earlier.

Later, the Navy offered a smaller, more fitting tribute to the sailor who had spent so much of his life at sea. Ross again went to sea one last time aboard a ship named Nevada — this time a submarine, for his burial at sea, and his ashes poured over the side directly above his ship, the battleship USS Nevada, resting far below.

Happy Birthday Captain Ross. We remember your service, and we honor your memory.

Read more about this naval hero here.